Article by Prince Tettevi, Engagement and Research Manager, Ghana Fintech and Payments Association

Even as Ghana’s formal financial inclusion rates climb, a persistent gender gap undermines the full economic participation of women.

The 2025 Global Findex Report reveals that while 36% of Ghanaian women now save formally, a figure that has nearly doubled since 2021, men remain 7 percentage points more likely to do so.

This disparity is fueled by structural barriers including lower digital literacy, less confidence in digital security, and reduced independent decision-making power in financial matters.

For generations, the traditional Susu system a term meaning “little by little” or “to plan” in Twi has served as a critical counterweight to this exclusion. It is not merely a method of saving but a community-based framework for pooling and sharing resources for collective benefit, rather than for profit.

Operated largely by and for women who face hurdles engaging with formal banks, Susu strengthens social cohesion and fosters enduring community ties, creating a parallel financial ecosystem that remains vital to millions.

This ecosystem is not a monolith but a diverse network of models with varying levels of formality. These primarily include:

- Susu Collectors: Individuals who collect daily deposits from clients and return the accumulated sum at the end of the month, minus one day’s deposit as a commission.

- Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs): Groups where members contribute a fixed amount to a common pot, which is then given in full to a single member each cycle.

- Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations (ASCRA): Groups where contributions are accumulated into a fund to cover lump-sum costs for events like funerals or ceremonies.

- Susu Companies: More formalized, registered entities that, in addition to savings collection, provide loans to clients after a minimum saving period.

In a strategic move to formalize Ghana’s informal finance sector, the Bank of Ghana in 2011 established clear regulations for Tier 4 operators, including susu collectors and money lenders. Under this framework, all operators were required to register with an umbrella association like the Ghana Cooperative Susu Collectors Association (GCSCA).

While there was no minimum capital requirement, registered members were mandated to contribute to a collective Insurance Fund being a key prudential safeguard designed to mitigate operational risks.

The rules focused on creating oversight without stifling function. Susu operators are restricted to defined geographical areas and were required to limit activities to core services like Susu collection or money lending.

Crucially, the Bank of Ghana delegates supervisory responsibility to the associations, requiring them to collect and submit member statistics periodically. This pragmatic approach integrates informal finance into the formal system, enhancing consumer protection while preserving its vital role in financial inclusion.

However, this resilient informal sector now navigates a complex labyrinth of modern challenges, from the disruptive force of digital finance to mounting operational and regulatory pressures, raising questions about its long-term viability and role in the financial landscape.

The traditional Susu industry is under mounting pressure to adapt. The rapid rise of Mobile Money poses an existential challenge by offering instant, digital savings and transfers without the need for physical interaction, directly competing with the convenience susu once uniquely provided.

Furthermore, the industry’s informal structure exposes it to significant physical and financial risks, including theft, fraud, and mismanagement. A single default by a contributor can irrevocably erode the trust that serves as the system’s foundational capital.

Beyond these operational vulnerabilities, the susu model struggles to meet evolving client demands. Customers increasingly seek more sophisticated financial services, particularly access to credit. Yet, the industry largely lacks the infrastructure for formal, risk-based lending, creating unmet demand and missed opportunities for growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst, accelerating a necessary but difficult digitization within the sector with many operators now using mobile money rails for transactions and software to replace physical passbooks. This has improved transparency and reduced cash-handling risks.

Nevertheless, the situation presents a complex dilemma. A susu system that fails to modernize risks being rendered obsolete by more efficient digital alternatives, potentially excluding the very demographics it currently serves.

An aggressive push toward formalization could strip susu of the community-based, trusted nature that is its source of resilience. The system thrives on its profound social embeddedness, providing a trusted financial pathway for women and low-income earners. The challenge is to find a solution that preserves these core benefits while integrating it into a modern financial architecture.

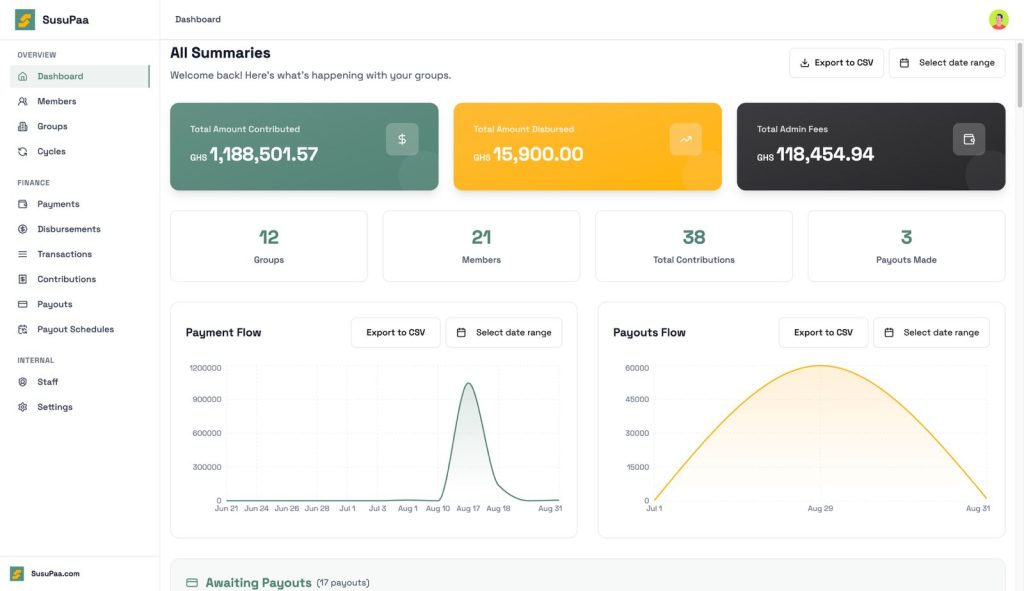

Platforms like SusuPaa are achieving this balance by digitizing the centuries-old tradition without severing its community roots. It alleviates the administrative burden on group leaders through strategic partnerships with licensed fintechs for payments, ensuring compliance while protecting the vital human relationships at its core.

SusuPaa strengthens the system by automating key processes like contribution reminders and real-time analytics. This enhances efficiency and transparency, providing modern tools while ensuring the system remains anchored in the accessible, community-based tradition that has always been its foundation.